Parenting expectations evolve faster than ever. If you’re raising a child under sixteen, you’re part of a special breed.

Every generation of parents has had to navigate a changing world, especially when advice from older generations doesn’t fit today’s reality. As a person born in the 80s, and being raised by multiple sets of parenting approaches, I’m battle-tested, but when it comes to parenting, I have more voices in my head than James McAvoy in Split.

TLDR; Follow my Instagram for bite-size versions of my blog posts!

My 9-year-old recently stopped me cold with a thought: ‘You’re trying to turn me into you! You just want me to work hard and have no friends, like you.’ He was in a highly emotional state and subconsciously I knew how we got there, but I was in my own emotional state and I was grasping at any thought that would calm us both down.

What put us in this situation? Homework.

We have a routine we follow every day to hopefully complete homework as efficiently as possible.

- Get off the bus

- Eat a snack

- Sit down

- Get to work

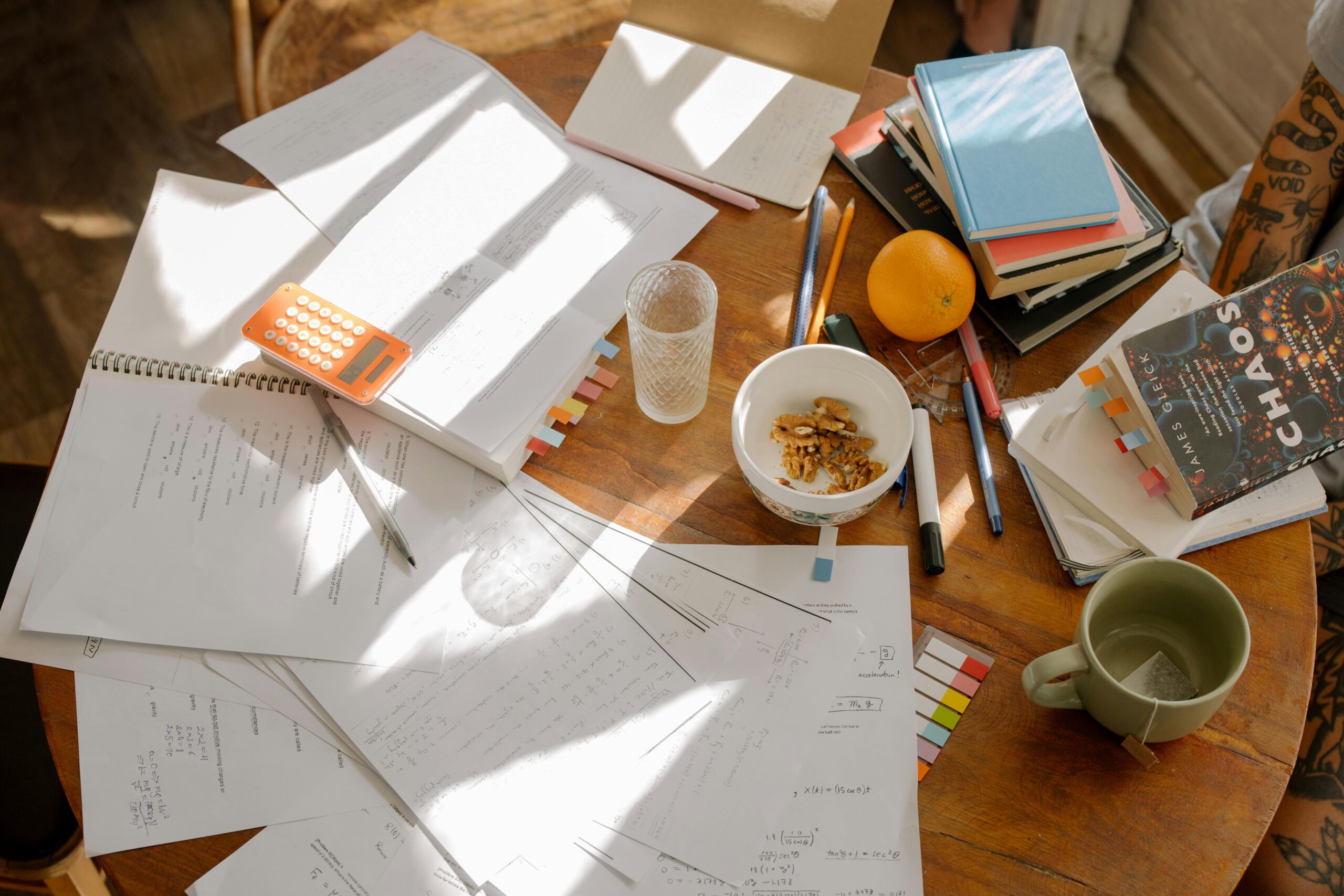

While he is eating his snack I’m emptying his backpack and looking for any assignments that need to be completed. A mixture of math, reading and writing will be laid out at the kitchen table.

This is where I set expectations and make sure to include, “And remember, Dad is still on the clock working. So complete what you can and then we can go over what you need once I’m done.” I walk back to my office and begin knocking out tasks, knowing full well what I’ve said went in one ear and out the other.

Not 2-3 minutes later does my son come to me with some sort of impediment to completing his task:

- “My pencil broke.”

- “I don’t understand this first question.”

- “Someone is calling on my tablet, can I answer?”

This is where I take a deep breath, because in the back of my head I’m already annoyed. This is where the voices come in.

- 1950s parenting says, ‘Figure it out yourself, or you’ll never survive the real world.’

- The 1980s voice: ‘Just give it to me, I’ll do it.’

- The 21st century voice: ‘Aww, let’s work through it together—you just need a little help.’

Each voice will jump into the spotlight and try to take over, but every time this happens it’s a struggle. It isn’t my son’s fault. I, like every other parent out there, am just trying to figure this thing called parenting out. There was no class or manual and I remind myself that every day.

I use an approach for everything in life: fail, fail, fail! It’s all about experimenting. Test with every approach, every thought process, snack, trigger, and reward. If we can control it, we will constantly tweak it and go until failure.

I’ve spent over 20 years as a software developer and the only reason why I was bestowed the title of Lead was because I’ve failed so much I knew what not to do and how to pivot when things started going in the wrong direction. Now I apply this approach to parenting.

MVP: Minimal Viable Parenting

When engineering any new project or process in software it is important to define the goal well and then come up with a prototype. The prototype is something that is so small and easy to implement that you can test and learn from it as quickly as possible. At its core, this approach is to push to failure, learn from it and then tweak it.

So how does this work in my parenting style?

The routine we use today is actually version 5. The prototype was when we started homework right after we got off the bus. We used to have a lot of issues getting homework done as a whole, but when we kept him in the school mindset and showed the reward of uninterrupted time to unwinding afterwards, we were able to get it done with minimal fighting. This was 2 years ago, when the homework was a lot easier.

Version 5 added the snack right as he got home, because he was always asking for them during the homework and we often used it as a motivator for getting a question right. We even changed the snacks he is allowed with this major version update. Anything that contains glucose is what we try to stick to. Primarily since our thinking brain uses glucose for fuel.

We adjusted our approach because there is more homework and it requires him to think harder. Word problems, note taking while reading and increased vocabulary is now a daily occurrence.

As the brain power requirements increase to complete the task the approach needs to evolve.

This approach can work for anyone because there’s no right or wrong. The only wrong move is refusing to try something new. Staying open with yourself and your child builds better critical thinking for both of you. Be open to share feelings, because that is a real time data point that can help give insights on what is working and what isn’t. Don’t shy away from the uncomfortable though. This is where progress is made.

Here are steps we follow to try out an MVP improvement:

- Identify one specific problem and/or trigger.

- Discuss and explore different options to solve this problem. Three possible options is a good target and don’t let all of it come from either side.

- Agree on a solution and create a prototype to test with.

- After you test the prototype, discuss if it felt like you were achieving your goal.

- If it was a success ask questions about how it could be better.

- If it was a failure ask why around 5 times to get to the root of the issue and then try another solution.

Conclusion

Don’t judge yourself on how far you are from the goal, but how much you’ve improved from the start. Keep working together and build an understanding that it’s a partnership and that it can’t get better without them.

What are you going to test next? Share it in the comments below.